- Home

- Belinda Pollard

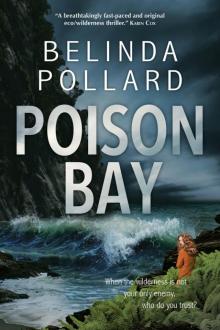

Poison Bay Page 2

Poison Bay Read online

Page 2

Jack nodded. Next to Kain, he saw Sharon bend her feet up and back, looking at her cheap boots. “Do you know why Sharon didn’t buy the stuff on Bryan’s list?”

“Apparently she used Bryan’s check to pay her credit card bill before she discovered how much this gear costs.”

“Understandable, when she’s got a little kid and no husband.”

“Yeah.” The tired eyes became lively. “I could have punched Bryan when he made her cry about it last night, carrying on as though her life depended on a few clothes.”

“I know what you mean. But I guess he’s under pressure to keep us safe. It’s dangerous out here—avalanches, blizzards, wind storms, flash floods, the works. Did you know they get about seven meters of rain a year? It’s one of the wettest places on earth.”

“Really?” She raised an eyebrow. “Not something Bryan bothered to mention in his invitation.”

He laughed. “Enjoy the sunshine. You might not see it for a while.” He became serious. “What do you think of the trek he’s planned for us?”

In last night’s briefing, Bryan had given almost no details about their route, except that it would take ten days to reach world-famous Milford Sound but stray far from any existing tracks. They would begin on the rarely-used track to George Sound, and that was the destination they would mention to anyone who asked. After a couple of days, they would head off-track into deep wilderness. Bryan wanted to create a brand new trail in honor of his dead parents. He’d tested the route himself, and now it was time for a group of hikers to confirm it. They’d been ordered to keep their goal confidential.

Jack said, “Why choose us to test something like this? We’re not exactly trailblazers. And why does it need to be hush-hush?”

“He must be trying to protect the naming rights or something. Can you imagine if we asked him to change the itinerary now? He’d probably grab an ax and kill us all. I’m hoping it won’t be as hard as we think. But at least we’re carrying our own body bags if we need them.”

Jack grimaced. Apart from providing waterproof storage, the huge orange plastic bag in each of their kits was big enough to contain an adult in an array of scenarios, the color designed to catch the eye of searchers. He said, “They’re very useful looking bags, but Bryan didn’t need to be quite so grim.”

“Never fear, I’ve got duct tape if anything goes wrong.”

Jack smiled. “You too?”

“I’m a seasoned traveler. But seriously, we’ve got the satellite phone and emergency beacon—and he did notify the authorities. Surely that’s a safety net.”

Bryan had told them he’d registered at the Department of Conservation office. Someone would start looking if they didn’t come home.

***

Their “track” was nothing like the one he’d hiked with Bryan all those years ago. At the time, he’d thought it rough compared to Australian trails. But that scrappy gap in the rainforest seemed like a city footpath in comparison to what they were walking today.

The occasional orange triangle nailed to a tree was the only way to tell they were even in the right part of the valley.

Most of it was an undergrowth-infested bog. Some of it was ankle deep in water. Today’s weather might be glorious, but it had obviously rained yesterday. Hard. And probably the day before and the day before that.

They clambered over fallen trees and boulders the size of cars. Not for the first time in his life, Jack wished he was taller. To scale the larger rocks, he had to reach up so far his arms were almost fully extended, then lift the combined weight of his body and rucksack. The women were being helped—a leg up from below, a hand reaching down from above. But he couldn’t ask for that. The other blokes were managing.

Long tendrils of hairy lichen hung from the trees, glowing in slivers of sunlight. They tugged at his arms, slapped his face.

Waterfalls hurled themselves down slopes so steep they were virtually forested cliffs. The group ate lunch near a place where the vegetation had apparently lost its courage and let go, laying bare a strip of granite wide as a freeway and one hundred stories high.

“What caused that?” Jack said to Bryan.

“Tree avalanche. They happen after heavy rain.”

Later, they crossed the river on an instrument of torture some joker had deemed a bridge: three steel cables suspended above rushing water, one to walk on, two higher ones to steady yourself. The drop to the sharp boulders and rushing water were bad enough, without the wobble in the wire as he edged across. Even worse, he was forced to wait till last, having been appointed by Bryan as today’s “sweeper”, watching to make sure no one was left behind.

As they made camp in the soft evening light so many agonizing hours later, Jack watched Callie laugh with Kain, and drew ungracious comfort from the suspicion that the other man was hurting from the day’s ordeal.

Kain helped Callie and Erica set out their tent, while they discussed the pleasures of a wilderness without spiders or snakes. Kain said, “No bosses, either. It was the sweetest thing being able to tell him there’s no phone signal out here as I left the office. You should have seen his face.”

Erica said, with a hint of snarkiness, “Why do you stay in that job if you hate it so much?”

“Maybe I won’t. Those ‘golden handcuffs’ might lose their power any day now.”

Jack wondered how often those rippling muscles did anything useful. He had always privately thought Kain’s voluntary work as a surf lifesaver was mostly about being a hero in front of women in bikinis.

And he was going to have to share a two-man tent with him tonight. Rather than use bunks in a conservation hut, their fearless leader insisted they get into practice for the rest of the trek.

Today’s ordeal by jungle counted as a “marked track”, even if it was rarely used. Where they were going, there were no huts. No track. No shelter other than what they carried or nature provided.

Bryan called for their attention. “A trace of mud in your tent each day will become a pig sty by the time ten days are up. The cloth in your kit is to keep everything clean. Use it. Thoroughly. Every night. Wash it in the river each day and hang it on the back of your pack to dry as we walk.”

“Yes sir!” Adam saluted, drawing a few giggles.

Bryan gave him a cold stare, then continued. “Leave nothing outside your tents. When you go to bed, wipe down your boots and take them inside, or you’ll be walking barefoot tomorrow.”

“Why?” said Sharon, wide-eyed. “Will someone steal them?”

It was a strange question, since they’d seen no other human since the boat that brought them across the lake turned back to Te Anau, breaking any connection with civilization.

Bryan harrumphed. “Keas. Mountain parrots.”

Everyone waited for him to elaborate, but Bryan returned to the dinner preparations.

Jack moved to a vantage point, his camera capturing soft colors and moody mists in the distance.

“You’re taking a lot of video.” Callie was suddenly beside him, her own camera pressed to her eye as she rotated the zoom on the big lens.

“I’m thinking about making a documentary.”

“For the web?”

He shrugged. “Web. Television. Haven’t decided.”

“Not for television.”

The energy of his answer surprised even him. “And why not? Is mediocrity illegal now?”

She blushed. “You can’t make a television documentary with a little camera like that.”

“What do you think freelance journos who go into closed areas do? They don’t take fourteen technicians and a makeup artist. They take a camera any tourist might carry, so no one will stop them at the border. They shoot their own pieces to camera by sitting on the ground and holding it with their feet if they have to. I’m not trying to be Attenborough, just tell a story.” He shoved the camera in his jacket pocket and turned back to the campsite, embarrassed and off-kilter.

Later, the weary group made quiet con

versation around the campfire, a fingernail clipping of moon hanging overhead. With a warm meal of reconstituted food in their bellies, snug tents awaiting them, and their weight off their feet, the contentment was tangible.

Jack said, “I had no idea those dehydrated things could taste so good.”

“Sure beats crocodile,” drawled Adam.

Sharon said, “Have you really eaten crocodile? Yuck!”

“No, but I had to shoot one last month, to stop it eating a customer. We didn’t put it on the menu. They eat rotting meat. Store it underwater somewhere until it’s ripe.”

A groan of revulsion rippled round the circle.

“I ate crocodile once,” Kain said. “Big overseas client. One of those posh restaurants with main courses for $100, emu and ostrich, that sort of thing.”

“What did it taste like?” Erica said.

“Actually, it tasted a lot like chicken.”

Jack muttered, “Probably was chicken.” Callie apparently overheard him, and stifled a laugh. Their eyes met and Jack felt the awkwardness between them ease.

The sky was clear, the air crisp. Eight people alone in the universe.

Bryan said, “The Maori call this place Ata Whenua—Shadow Land.”

Rachel said, “Why is that?”

“The mountains are so steep that in winter some of the valleys never get the sun.”

Like many of Bryan’s comments, this one shifted the tone. “Great,” Callie said. “Does anyone else feel like those mountains are watching us?”

Adam said, “Nah. It’s not the mountains, just the mountain parrots.”

Jack chuckled, but stopped when he caught a glare from Bryan.

Before long, the hikers dispersed to their assigned tents. Bryan had separated friends and combined people who didn’t get along, but whether he’d done it as a mixer or for less cuddly reasons, who could tell? Jack was sure Callie would have preferred Rachel to Erica. As for him, despite being housed with Kain, he wriggled into his sleeping bag with a vast sigh of relief. It was bliss just to lie down.

***

Morning brought sullen skies, scudding rain, and even flurries of snow. Jack found the cold amplified yesterday’s muscle strains as he forced himself to walk again.

Adam was about to cross a creek ahead of him when a rain squall hit them full in the face, sending them fumbling to raise jacket hoods. The other man turned back to say, “Great holiday, huh?”

“Yeah. Who’d go to the beach when you could do this?”

Hours later, they prepared to lunch on the last of the sad little sandwiches made yesterday morning. With difficulty, Jack persuaded Bryan to authorize the gas stove for instant soup, to help comfort them in the bleak weather. The meal was eaten huddled under thick tree cover that stopped much of the rain, or at least broke its fall.

Jack sheltered Rachel’s hands with part of his jacket while she checked her blood sugar, and beside her, Erica strapped her knee, using a first-aid kit she’d brought from home. “Are you okay?” he said.

She shrugged. “It’s the twisting and turning. I’ll be okay.”

He was impressed by the discreet way she went on to dress Sharon’s blistered feet. Sharon didn’t need Bryan’s criticism for buying the wrong shoes, to add to her physical pain.

Later, his respect for Erica dissolved. She flirted with Kain all afternoon, and Kain reciprocated. They were welcome to each other, but Jack was pretty sure they were doing it to taunt Callie. She’d become unusually quiet.

When the time came for lights out, he went to the tent he was to share with Kain, but his pack had been dumped in the rain. Erica had taken his place inside.

“Where am I supposed to sleep?” He felt a ridiculous desire to report them to Bryan.

Kain said, “Go and share with Callie, Reverend. You’ve always wanted to do that anyway.” He tossed Jack’s sleeping bag out, and pulled the tent flap down in his face.

Jack stomped over to Callie’s tent. “Knock, knock.”

“Who’s there?” She stuck her head out.

“Your new roommate. Erica’s taken my spot.”

“I wondered where she’d got to.”

“I’m sure it’s going to be a very deep relationship, for about eight more days.”

“Well you can’t sleep under the stars in this weather, so you’d better get in here.”

Jack crawled in after her, and wrestled with his rain-spattered sleeping bag. By the time he’d got himself settled, he’d become philosophical. “This might be better anyway. Kain snores.”

“Wait till Erica finds out,” she said, her voice muffled by her sleeping bag. “Better still, wait till Bryan catches them.”

“Do you think they’ll get detention?”

“At the very least.”

“Hey, what if Bryan catches us?”

“We’re not going to do anything. Trust me.”

“Yes, but if he sees us coming out in the morning, how will he know?”

“Bryan is weird, Jack, not a moron. He’s had to watch those two all afternoon, same as the rest of us.”

“I suppose so. But don’t you try anything. I’m a good Christian boy y’know.”

Callie giggled. “Oh shut up and go to sleep.”

After a few minutes silence, she spoke again, her voice soft. “Jack, about those foreign correspondents… you might be right. I’m sorry I was dismissive about your camera.”

He blushed in the darkness. “Don’t worry about it.”

“It’s just that I’ve been used to different production standards. My doccos are always about things that happen in nice, safe places.” She snorted in self-deprecation. “With electricity and plumbing.”

“I’m sorry I lost my temper. I guess I’m not sure I know what I’m doing.”

“I never had any doubts about you, only the camera. Everything you did when we were at school and uni was excellent.”

“Flattery doesn’t work with me, Cal.”

“It’s the truth. If you believed in yourself more, you could do anything.” She sighed. “I always felt inadequate around you, to be honest. It’s all smoke and mirrors with me. Day after never-ending day.”

He fought the urge to reach for her hand in the darkness.

4

Ellen Carpenter was working late again, because work filled the hours. She knew she must go home, or run the gauntlet of the muggers that populated her imagination when the university campus grew dark and creepy.

But her Brisbane home was silent too, tonight. And so she lingered.

On her desk, three faces smiled out of a photo frame; her own between Roger’s and Rachel’s, a family holiday at the Great Barrier Reef. Was it only two years ago? Before they even knew anything was wrong. Before she noticed the dark blotch on her husband’s back.

Thanks to Ellen’s encouragement, her only child was on the other side of the Tasman Sea tonight, engulfed by wilderness, while her mother tried not to worry about the dangers and whether she’d packed enough supplies to manage her diabetes.

And Roger was so much further away than that.

Ellen turned to her calendar and calculated the number of days before Rachel came home.

5

With every day that passed, Callie’s anxiety grew. Why had she agreed to come? It was so much harder than she’d imagined back in the lunchroom at work, telling her colleagues stories of daring and danger, while not really believing them herself.

Now she was living the reality of her foolish decision. There were times she wondered if she would survive. She had followed Bryan’s instructions and trained till her body ached, weekend after weekend in the Blue Mountains near Sydney. But she was no athlete, and now her body was betraying her. Every muscle and ligament seemed to be debating its level of commitment to her bones. Her thighs turned to jelly on the downhills. On the uphills, her heart roared in her chest, to the point that she wondered how many twenty-seven-year-old women had heart attacks. Her shoulders and neck throbbed from t

he dragging weight of the rucksack. She counted down the hours and minutes till the next break, when she could ease it off her back and plonk it into the mud for short-lived relief.

At lunch on Day Three, she tried to talk to Rachel about it.

“I’m not coping. I don’t know what to do.”

Rachel frowned. “What do you mean? You just put one foot in front of the other, that’s all.”

“I’m afraid, Rachel. We’re not even halfway there.” She felt tears gathering.

“Don’t be silly. You’ll be fine. It’s just walking.”

Callie felt abandoned. Dismissed. Misunderstood. Rachel had always been exercise crazy—her way of keeping a sense of control over her diabetes. She was forever at the gym, or cycling, or swimming, or hiking—she was a machine. She obviously didn’t have a clue what it meant to be inside Callie’s skin right now.

Callie was engulfed in a longing for home—not Sydney and its emerald harbor, the city she’d lived in for the past five years, but Brisbane. The refuge of childhood. In her mind, she saw its gently rounded hills, dusty gum trees, the sleepy brown river.

But most of all, she longed for its great big sky. There was no sky in this place. Just a narrow gap between granite cliffs overhead, and even that disappeared when the clouds fell down.

And fall they did.

The storm that descended later that afternoon had been busy beforehand, up in the tops.

Callie watched Sharon ahead of her soldiering onwards on ruined feet, sloshing through water shin-deep from the swollen river. Every step must be an ordeal for the poor girl, but Callie had yet to hear a complaint pass Sharon’s lips.

I’m such a coward. Tears slid down her face, and she didn’t care. In these conditions, who would see?

Rain pounded on her jacket hood, bounced off her rucksack’s rain cover. She became aware of a roaring noise, even above the sound of the rain. There were shouts from up ahead. Through the downpour she dimly saw people running. Uphill. Away from the river.

Poison Bay

Poison Bay